A life between London, Berlin and New York to eventually land in Rome. Where’s Art talks to British conceptual artist Thomas Hutton about his research and latest projects, digging into his choice to live in the Roman art scene and his relationship with the city.

“Reality is a very subjective affair. I can only define it as a kind of gradual accumulation of information; and as specialization. If we take a lily, for instance, or any other kind of natural object, a lily is more real to a naturalist than it is to an ordinary person. But it is still more real to a botanist. And yet another stage of reality is reached with that botanist who is a specialist in lilies. You can get nearer and nearer, so to speak, to reality; but you never get near enough because reality is an infinite succession of steps, levels of perception, false bottoms, and hence unquenchable, unattainable. You can know more and more about one thing but you can never know everything about one thing: it’s hopeless.” – From Vladimir Nabovok’s interview, Peter Duval-Smith and Christopher Burstall, BBC Television, 1962

Where do you work? And why, after years spent in New York, London and Berlin, did you choose Rome as a city to live in and develop your work?

For the past year I’ve been living in Rome – and working in a very particular place that could only be in Rome – a space on top of a section of Aurelian Wall and Acqua Marcia aqueduct, overlooking Termini’s 30-or-so tracks of train line. I could never have found this kind of context in any of the cities I have lived in before. Each city comes with its own particularities – its histories, types of space, its people, and attitudes. For me those conditions are important – they don’t only inspire thoughts in me but they bring meaning to my work. Ultimately, I think I was looking for the right context for my work to originate from. I see the environment that my artwork is made in as part of its material history.So many of the material or spatial conditions my work is concerned with originated from Rome so it seems like a good place to start. I suppose you could also say that it was a reaction to the cities I had been living in – a search for a deeper texture than London (that has become so polished), a slower pace than New York, or a quieter place than Berlin.

Do you think the place where you live influences your practice, and how?

There is less pressure from the market in Rome than there is in cities like London or New York. I feel like can focus on my work without becoming overwhelmed. For my particular circumstances and for this period in my life, this is a good place to be as an artist, but it is also a difficult place to earn a living and so I can understand why artists from Rome leave. There also seems to be a tendency amongst galleries here to show artists from abroad. But I think this is kind of a shame, there are so many great artists here, and the galleries and collectors need to be supportive of local artists in order to hang on to them.

What is your work about?

I am always hesitant to prescribe or fix its meaning. I prefer to keep it fluid. I think it’s always subject to change. It often changes for me as I make something, or when I install it, or re-install it. Certainly there are themes though; ideas or concerns that thread through the work. But they’re not always lucid. In fact I will often muddy the water. If you can see something clearly, if you feel like you understand it immediately, you are not as likely to keep looking at it, keep thinking about it. Whereas if you think you see one thing, then you see another thing, then another, you are more likely to spend a bit of time with it, thinking about it. Abstraction can be a useful tool for achieving this. So you could say that I’m more interested in setting up an experience. Usually that experience has something to do with the nature of how we perceive things in time and space. This is why I always describe all my work as sculpture, even if it might not necessarily look like one. It has all been conceived as a physical and temporal experience.

In your latest project “Under the Façade”, there seems to be an interest of yours in the idea of deception. Vladimir Nabokov was truly convinced of art’s dependence on deception. Would you think the same? Do you feel like expanding on this?

It’s interesting that you would mention Nabokov. I recently read somewhere that Nabokov was an eminent entomologist and that he had been involved in the organization of Harvard’s butterfly collection. Last month I was in Connecticut visiting my friend, the artist Jeffrey Stuker, who has been making some fascinating work at the Seeld Library about a mimetic insect called the Fulgora laternaria, whose wings contain markings that resemble the eyes of an owl and whose head rather remarkably resembles a crocodile. He has painstakingly been making a 3D digital model of a Fulgora specimen that is so life-like and detailed that it is difficult to imagine it as anything other than a photograph. So in one sense, he is using the technology to deceive in the same way that evolution has enabled the Fulgora to deceive its predators. Images can possess this power of deception and people have always marveled at this. I expect this is what Nabokov may have been referring to. But I wonder if he’d say the same thing now. YouTube is filled with videos of babies “swiping” and “pinching” over the pages of glossy magazines, confusing them to be touch screens. This kind of image fills me with terror. We are loosing touch with the materiality of things. As the screen recreates the world on its flat surface, so the built world seems to become evermore flattened. Materials are veneers and architectural spaces are determined through screens for the camera so they can return once more to the screen. These kinds of confusions are not old though. I see them in the cladding of façades in Rome or in the painted marbling of their interior walls. But whereas they reveal themselves on closer inspection – and even celebrate their own limits as images (think of the dome of S. Ignazio, for example), the deceptions of today have such depth that we are pecking at the fruit without really knowing if it’s real or not and so the very nature of the way we interact with things is evolving.

What is it in the world that mostly influences your work (music, horror movies, religion, books, economics, mass media, etc)?

My influences come from pretty eclectic sources. Anything I encounter has the potential to find its way into my work. I suppose that’s because I don’t separate my life and work. It’s all part of the same endeavor. I like to think of it as all part of one continuing investigation, one that I navigate in much the same way as a detective might pursue a case in a crime novel. I follow leads and hunches, meet with people, visit places, inspect things, look at evidence and try to make my own sense of it. Last week I had lunch with a zoologist and zoo historian to talk about the history of Rome zoo; I visited a Travertine quarry in Tivoli; and I travelled to Florence to spend the day looking at Fra Angelico’s frescos in S. Marco. I guess this is typical of the way I like to work. Books and films will only ever take me so far. At some point I have to go and see be in the place, see the things, meet the people. This is one of the reasons I came to Rome… I was tired of reading about Rome from New York.

Is there a technique/material you prefer and/or use more often, and why?

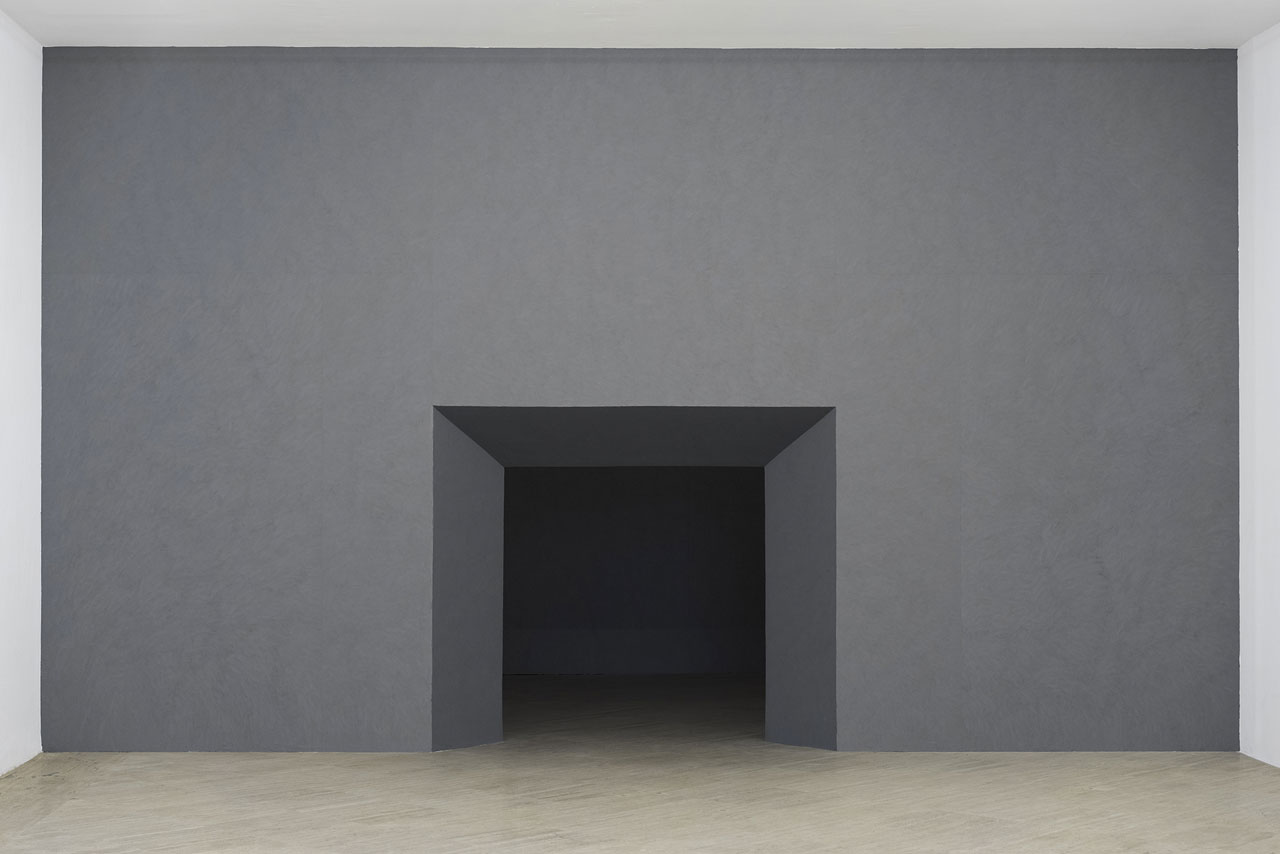

There isn’t really any one material or technique that I prefer to use but there are a number of materials I have been drawn towards thinking about and using. For the past few years I’ve been really interested in the decorative lime plasters applied to wall surfaces – or “stucchi” as they’re known here. These kinds of plasters have been used for millennia – they line the walls in the chambers of the pyramids of Giza – but Italy is certainly the place where it has flourished most. Astonishingly the material and its application method are almost completely unchanged since antiquity. If you read Vitruvius’ description of how it was applied two thousand years ago, it is identical to the technique you’d find being demonstrated on a YouTube tutorial video. This kind of layering of history that a material or technique is capable of is fascinating to me. I’ve been really drawn to travertine since being in Rome for similar reasons. The monuments of imperial Rome were clad in travertine from Tivoli, then the baroque churches adopted it; the fascist architecture of the 20th century used it in allusion to its imperial history; and today it lines the lobbies of skyscrapers in Shanghai. I think it’s a really vivid example of how a material can be charged with meaning that goes far beyond its physical attributes; how it can become politicized.

What would you like the audience to take from your work?

I want to gently break their step. Give them an opportunity to slow down a bit. Encourage a quiet, acute experience that allows their perception of the thing that they’re experiencing to sharpen as they experience it in time. But not so they can understand it, but so they can have a kind of dance with the idea of a thing. We don’t get to have those kinds of moments very often. I think they can heighten the way we experience the world, make us more aware.

Among your recent shows, you have participated in the independent project “There is No Place Like Home” that has been hailed as one of the most experimental exhibition project in the Roman art community. How would you describe that experience?

I was really pleased to be involved in “There is No Place Like Home”. It was the first time that I showed my work in Rome. I don’t think there could have been a more fitting first exhibition in Rome – my new home – than to show my work amongst new friends in an unfinished house. It was a brave project that Alessandro, Stanislao, Giuseppe, and Marco embarked on. It was exciting to discover those kinds of shows could happen in Rome; that there were people willing to take big risks. You had to sign a liability waiver to enter it!