“Well received lies”, the exhibition of Norwegian artist Henrik Olai Kaarstein presents multifaceted artworks in the new premises of T293 in Rome. Black and white images, colour intensifying subjectivity and installation lead viewers to explore love as well as political relationships, activating a reflection on their own condition. Are these all well received lies?

Fortunately a human being can comprehend only a certain degree of unhappiness; anything beyond it destroys him or leaves him cold. There are situations in which fear and hope become one and the same, cancel one another out, and lose themselves in a dark insensateness. How else could we know the people we love best to be in continual danger and yet go on with our daily lives as usual? ― Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, Elective Affinities

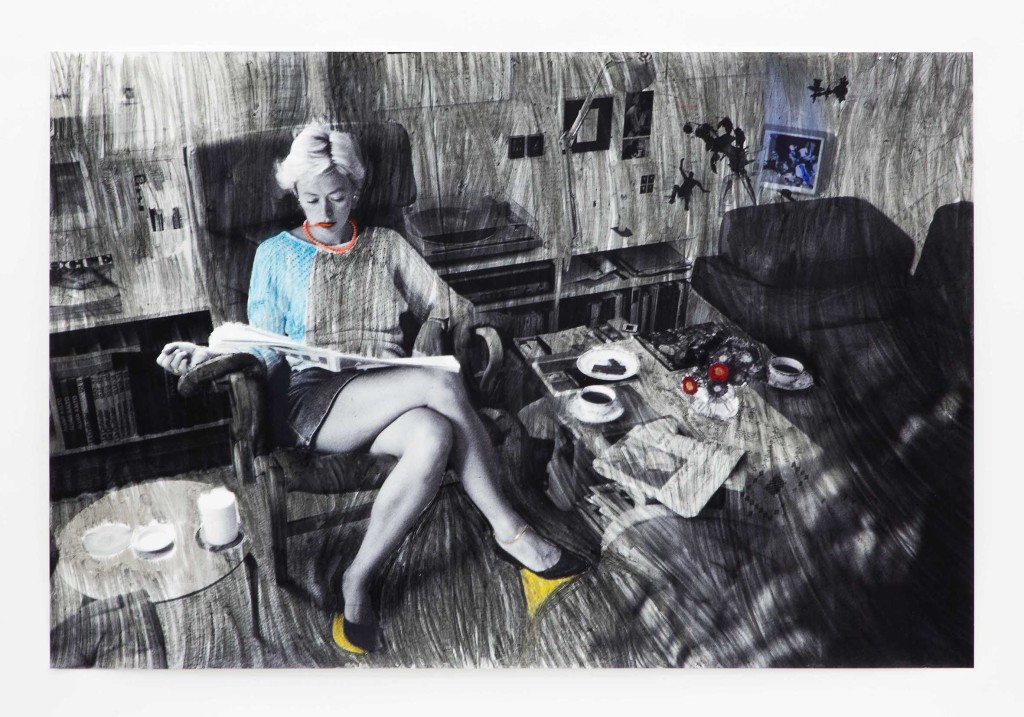

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, ‘Villa Moderne, Arcueil’, 2016, charcoal, soft pastels on inkjet print, 150 x 225 cm. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

In the exhibition “Well received lies” we can observe human figures, sometimes isolated in the composition, and at times in relation with each other. My sense is that when people are represented singularly, they convey a sort of anxiety. Their expression reveals their thoughts, leading to somewhere (or someone) else. In the case of portraying relationships, both private and public, it seems as if you use another approach. These processes lead to impactful results. Could you tell me more about your idea of Well received lies in relationships, and how you started focusing on this theme.

None of the motifs are represented isolated. I am in the room holding the camera, so I guess they are conveying an anxiety to me, or to the room and interior. Being photographed makes you anxious. Myself, I never know what to do with my mouth. Fish mouth or pouting lips? You can rarely recognize yourself in an image and you have the sense of not looking at yourself, like you would do in a mirror. On the other hand you have these black and white stills from movies, with actors and actresses that know what to do, captured in a continuation of a film and not in a moment like my private collection of prints. I’m still wondering who poses the most, the professionals or the subjects of my snapshotting.

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, ‘Everything He Does, You Do Better’, 2015, mixed media on fabric and paper, 290 x 250 cm. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, ‘Here Comes Iris’, 2016,

wedding dress, prints, fake roses, dimensions variable. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

I am curious about what lies behind titles such as “Everything He Does, You Do Better” and “Here Comes Iris”.

I always bring around my notebook, every time I leave my apartment it has to be with me, because I am afraid that these phrases that pop into my head will disappear. All these sentences are part of some unorganized collective poem. The writing I’m working on is reflected in the titles, and vice versa, It’s like the chicken or the egg. A sentence or a word is given to a title, a title becomes a stanza. So I organize, rearrange and deconstruct for whatever project I am working on to create a wholeness and a narrative that fits the theme of the show, and what I would like to project with an installation of works.

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, “Well Received Lies”, installation view at T293, 5 April – 14 May 2016. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

I am particularly interested in the techniques you used, and in mixed media. The images you found for this project were originally conceived and staged to be included in the exhibition or did you decide to use them in a second moment?

Everything I do is a mix between a set plan and embracing the spontaneity. I know exactly what I’m doing in the progress, but the outcome is rarely what I set out to do.

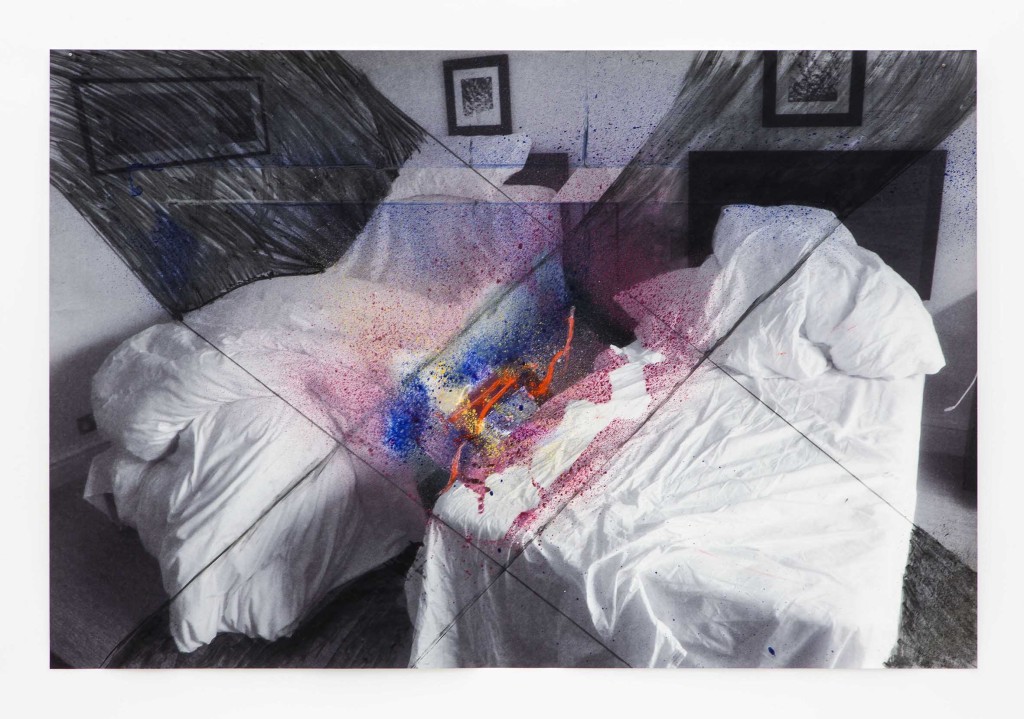

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, ‘Hyatt Regency, London’, 2016, charcoal, soft pastels, acrylic paint on inkjet print, 130 x 195 cm. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

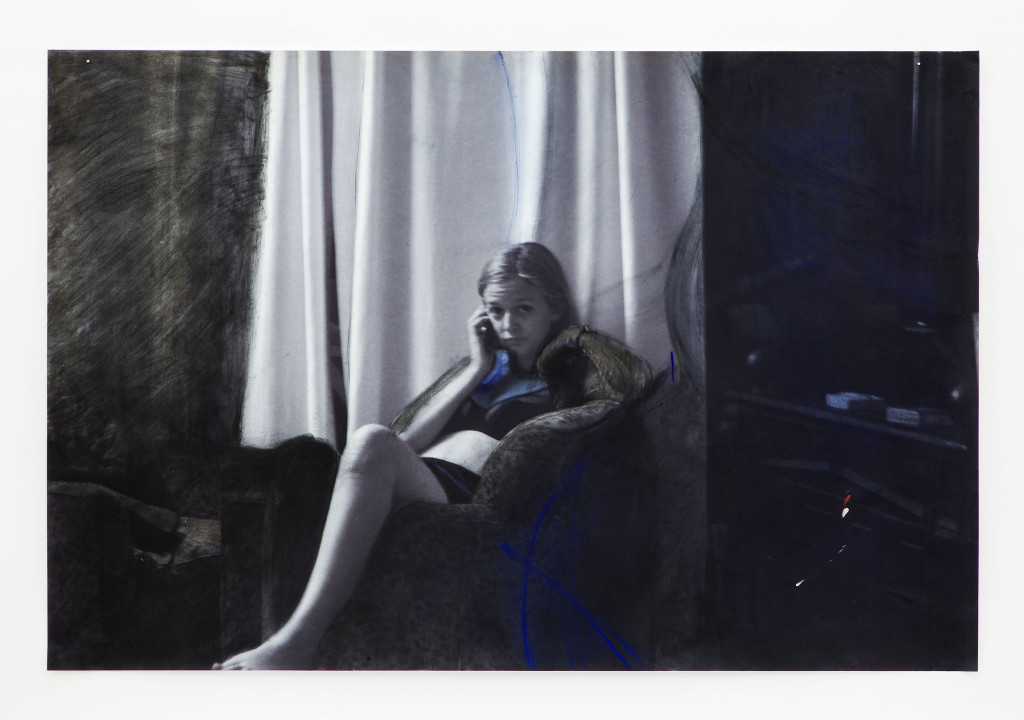

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, ‘Portrait: Undisclosed Location’, 2016, charcoal, soft pastels on inkjet print, 150 x 225 cm. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

The use of chalk and coal on prints produces captivating effects. Have you extensively used this technique in the past?

I always worked with the motif and idea of abstracting reality. A black and white photo is that by default, you know, reality is in colour

Charcoal is a tricky and strange material. I remember first applying and doing entrance examinations for art schools. There was a focus on black and white still lifes and nude drawing. The use of charcoal is somehow archaic and traditional, a very heavy and connotated medium in a sense.

It is such a difficult material to use, it spreads out too easily, but can never be completely erased. There is a lack of preciseness in it, although it is classically used to portray something figurative. It blends into the material in a beautiful and complicated way, still, on these prints they are always on the surface to remove and cover certain information. Like when a document is leaked from whatever agency or government, the names and places are censored in black. These works hands you information, but also gives you the middle finger, the viewer can’t have it all. It nearly felt sexual even working on these, being on all fours in my studio, using my hands to spread this grey powder over this sentimental imagery.

Concerning photography, I started my pubertal artistic pursuits with a camera:

“I tried taking pictures, but they were so mediocre. I guess every girl goes through a photography phase. You know, horses… taking pictures of your feet.”, Scarlett Johansson says to Bill Murray in that Sofia Coppola film [Lost in Translation].

Someone asked me why these prints are not just shown as photographs, they could, and painting and drawing over them is not to elevate or beautify them into something better, but it would be completely different works if they just existed in the gallery as an untouched status quo.

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, ‘Portrait: Roma’, 2016, charcoal, soft pastels, acrylic paint on inkjet print, 150 x 225 cm. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

I would like to know more about your relation with drawing, painting and installation. How would you say media and technique have differed (or evolved) from your previous projects to this one?

I don’t want to be stuck or feel comfortable or in control in what I’m doing, but also keep the sentiment of my past works into the progression and new works.

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, “Well Received Lies”, installation view at T293, 5 April – 14 May 2016. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

Henrik Olai Kaarstein, ‘What a Fool You Are to Fall So in Love’, 2016, mixed media on fabric and paper, 335 x 205 cm. Photo: Amedeo Benestante. Image courtesy the Artist and T293.

“Well received lies” is in the new premises of T293 in Rome. Some of the largest artworks in the gallery (mixed media on fabric and paper) are hung from the metallic structure on the ceiling of the gallery and create a sort of corridor of curtains, leading the viewer through an articulated path. I wonder how you felt working in this space.

I loved working in their new gallery space. It is such a nice venue. Very difficult for an artist to work in it, but simplicity is rarely that interesting. A tricky install period, and an unusual space give a certain energy that compliments my works.

I always wanted these large works to be hung in the room and reveal the back. The back is covered with dust, excess paint and revealing my signature in a coy and almost self-gratifying gesture. Many years ago I saw this pretty awful, second-hand marked exhibition of Basquiat. The works were fine, but he made these homemade frames and supports for the works that created this distance from the wall. If you walked close enough to the wall you could get a peek of all the toughness going on behind the canvas. The “wrong” side gave me such excitement.

Any exhibition I see to this moment I just want to pick it up and flip it over. I’m an ass person.

Fanny Nina Borel