Where’s Art talks to Italian artist Gabriele Porta about his research on human condition as well as his recent photographic and video projects exploring love, presented in the exhibition “Pure Love” at Rome-based Federica Schiavo Gallery.

The Unjustly Punished Child

The child screams in his room. Rage

heats his head.

He is going through changes like metal under deep

pressure at high temperatures.

When he cools off and comes out of that door

He will not be the same child who ran in

and slammed it. An alloy has been added. Now he will

crack along different lines when tapped.

He is stronger. The long impurification

has begun this morning. – Sharon Olds, Satan Says, 1980

I have just been kicked out my studio and now I settled in my house where there is a room I never used. I turned it into some sort of studio. I will shortly rent a new space that will be shared with a duo of artists.

What is your work about?

My work investigates a ‘middle territory’, a field that stems from the clash of opposite situations. I usually pick two apparently distant themes in order to develop a narration between them, often failing to control it. From this, also comes a friction that I am bound to unsuccessfully tame. I am usually into themes dealing with a very human condition, and with mankind in general. I am obsessed with life, its beauty and violence. I am constantly searching for something embedded in time and in our disintegration as long as we live.

Your work features an extraordinary ‘morbid beauty’, both in the subjects you delve into and in the technique and materials you use; we are thinking for instance at Ragazzi di Vita (2011) or You Take Care (2011). Can you expand more about this apparent oxymoron? And how would you personally describe the concept of beauty? The use of glitter also seems to recur in your work as well. What is its function?

This exhibition led me to a new understanding; actually, it was already part of me and my works for a long time. The oxymoron that encompasses the idea of two diametrically opposite things sticking together, also implies a certain symbiosis, for an extreme would not exist without its opposite. Therefore I like this dualism that completes itself, thus originating a whole.

I am not very much into the idea of beauty; I am much more attracted by a certain tactility of things than their visual aesthetics. I pay much attention to proportions and asymmetry. With regard to glitter, I see it as a way of obtaining different dimensions on the surface of my work. The gold of glitter reflects an ever-changing light, which I also want to be emanated by works telling about death or disintegration. This process starts from the color black, and ends with color gold. In between these two extremes is the space I explore. Darkness on one side, light on the other, I stand in the middle.

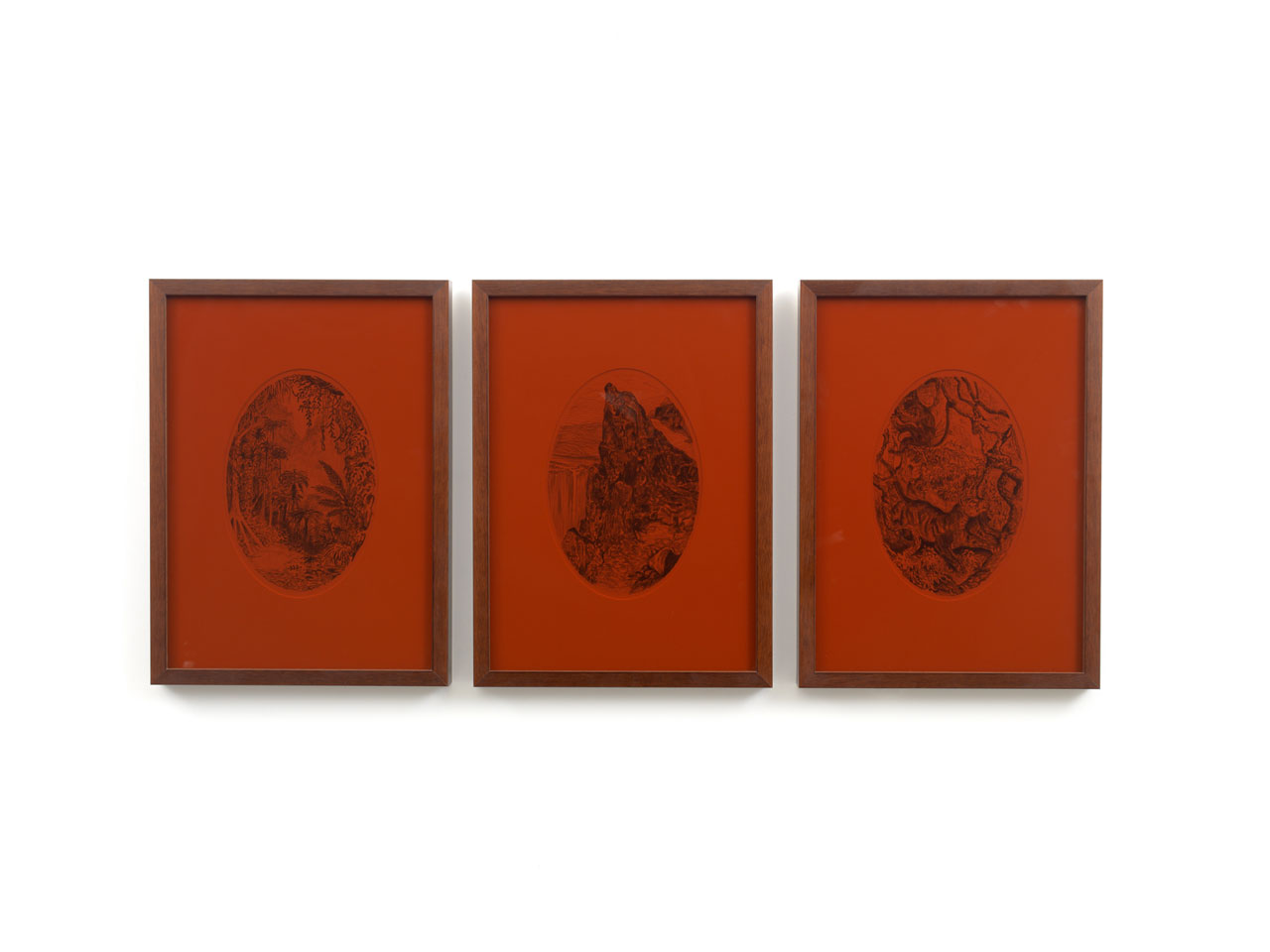

In your projects is a recurring use of historical material and documentary that you re-read and manipulate. Considering, for instance, images from the documentary about an aboriginal tribe of the Pacific in Untitled (First Touch) (2011), or illustrations from On The Origin of Species by Charles Darwin, that you have then worked so to create Looking for Beginning (2009), could you expand on how you work from archival materials and, what is the starting point for Untitled (Diaspora) (2014)?

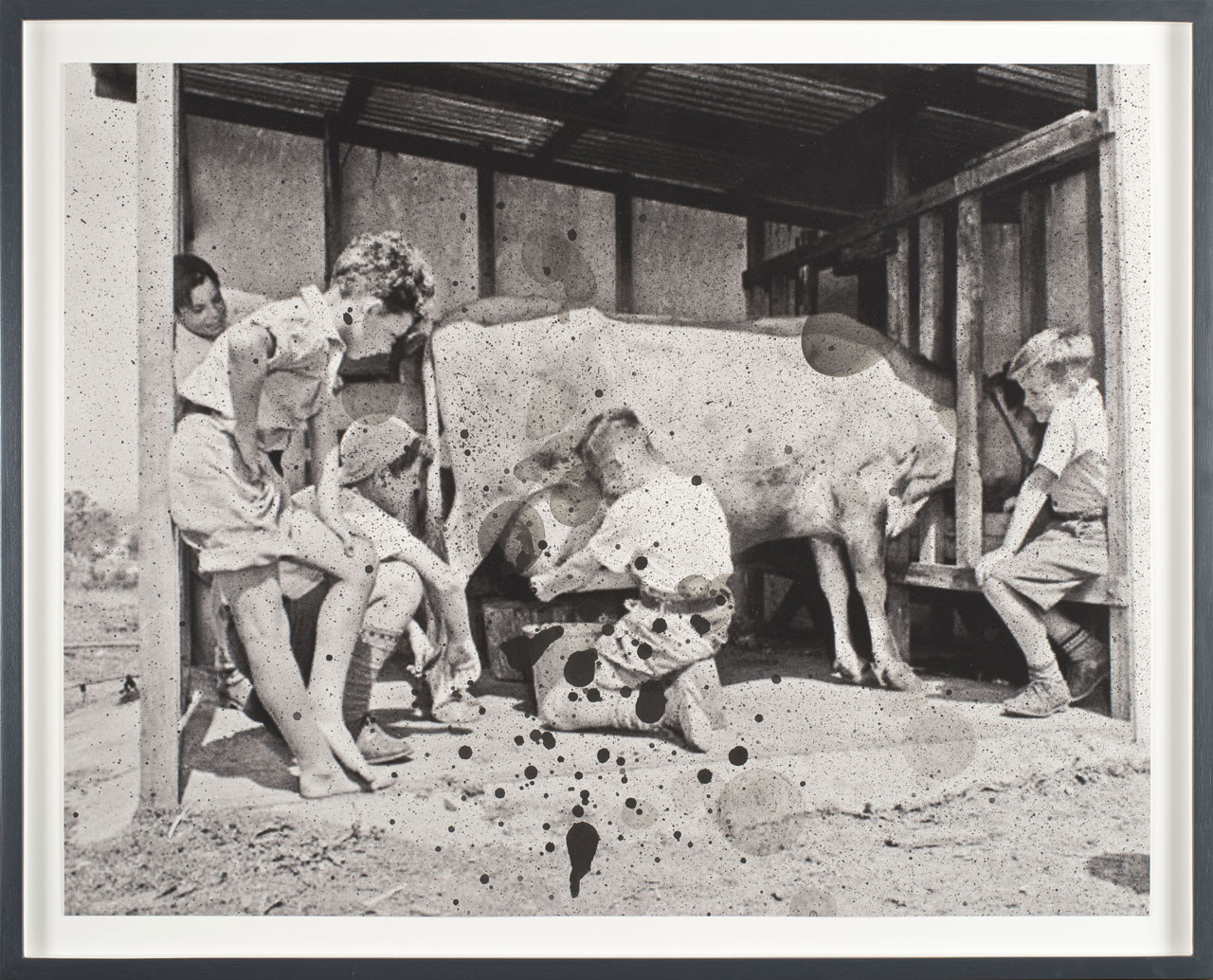

For the project Untitled (Diaspora) I was struck by history. The fact that right after the Second World War a generation of British kids orphaned by the conflict – or just because the parents could no longer look after them – was “deported” to Australia and New Zealand – as in a kind of forced Diaspora aimed at repopulating the Anglo-Saxon territories in Oceania – was something that fascinated me.

These children being torn from their birthplaces, with their family names erased and placed in institutions where they would become what the Australian and New Zealander governments would have liked, it was a somewhat questionable political project. In fact, sexual harassments as well as among the most horrendous physical and psychological abuses of all the history of the Commonwealth occurred in those institutions. When in 2006 the Australian government opened the archives of those institutes to help victims rebuild their past, I immediately explored these huge photo files depicting life in those orphanages. I have found some great photos where I blew soap bubbles over black ink. And the result was a very delicate work as soap bubbles are, but at the same time it was sad, dark, and oppressive as the abuse those children had to suffer.

I am kind of fetishist of certain vintage images as they have sort of taste of uniqueness; think of photographs or prints from mid-Nineteenth century. I am enchanted by an aesthetic that does not belong to me, perhaps that’s why they fascinate me. At this very moment, for example, I am kind of obsessed by Bilderatlas Mnemosyne by Aby Warburg, a huge archive of tables in which Warburg has collected hundreds of photographs trying to outline a precise path. A truly incredible, indeed hallucinogenic work!

How would you briefly describe your ongoing exhibition at Federica Schiavo Gallery?

It is a journey through life, sex and death, in a continuous fluctuation between pleasure and distaste. These topics lend themselves to multiple variations according to the interpretation one wants to give. I like visitors to make his way through with machete blows, looking for his own narration. In this process, he would face tenderness, violence, disgust, beauty, pornography and self-awareness.

In your show “Pure Love”, the parallel between explicit sexual drive and funeral rituals crosses the entire exhibition and recalls the dualism between Eros and Thanatos. These two fundamental forces animate human psychology, according to Freudian theory; is it this theory that you consider relevant to your search, as a starting point for this project?

Definitely. In this exhibition I was interested in investigating the emergence of certain human behaviors that begin to manifest with sexual maturation. In my opinion, violence and genocide are one side of the coin, on the other one is love and passion. That medal is the man, both male and female human beings. We are sort of a cycle: we generate the life, then we compel its completion, and ultimately we celebrate the death. That’s what we are. I was also drawn to Freud’s theory for that pleasure that leads to the idea of death.

To continue to explore this focus of your research, how would the projection of amateur video My Wedding Will Be A Funeral help enrich your discourse about love?

That video is about us; as man, we are there. I don’t mean as human beings in general, but as us ourselves: me, you, the reader of these lines, all of us. We are able to feel love for someone else but that feeling is reversed in the opposite manner resulting in hatred and violence. The psychologist Stanley Milgram showed it accurately before I did. In that video I just tried to combine these two opposite feelings in one image: a tender and innocent color clashing with images that have nothing to do with pureness.

You know there have been negative reactions to the projection of the video; what would you like the audience to take from your work? Do you ever consider the public’s reaction when you work on a new project?

I usually consider some people who mean a lot to me. I never think of the audience as a whole. When you are exposed, you should already know that part of people will not like the work, that’s part of the game! However, it is important to say that I approached with great passion at that video as I knew that what I was showing was a very delicate topic: you just touch it and it breaks. Thinking back, it is also like a soap bubble.

In Untitled (The Last Thought in Kid’s Lives is Love) – as in many previous works -, the series starring the age of puberty and adolescence, that you yourself define “a transitional age, an age that marks the middle of a birth, a transformation, a rebirth, an awareness of the Self through the union of suffering and pleasure.” Do you think this issue, so deeply emblematic of the concepts that characterize your research, will be further explored in some future projects?

I think so, it’s a strange time if you look at it through the eyes of an adult, there is some tenderness, a purity that makes you smile. Instead, through the eyes of a boy we see kind of the opposite, the insolence of being aware to begin to be sinners. This step is for me the ground that I explained before: first childhood, then adulthood. In the middle there is this time that it is hard to control. It’s like a jazz musician who knows the score, but then what excites him/ her is improvisation.